Published January 16, 2020 (Updated March 2, 2022)

John Cushing and Elizabeth Perlich Sweeney were close partners in improving medical care for children with heart disease around the world. John served as Children’s HeartLink’s international program director for almost three decades, and Elizabeth became president of Children’s HeartLink in 2002, leading the organization for over 10 years. (currently, she serves on the Children’s HeartLink’s board of directors) Together, John and Elizabeth led changes to our program and approach to care focusing on building capacity. Along with a dedicated team and visionary board, they made significant changes that allowed us to reach more children and improve the quality of their treatment.

“The only thing that we disagreed on was getting to the plane on time. Elizabeth is a last-minute traveler, and I am early to arrive,” laughs John.

Changing our approach

John became aware of Children’s Heart Fund (former name of Children’s HeartLink) in the 1970s. His introduction to the organization took place at the Metropolitan Medical Center in Minneapolis, where John was involved through his work in the health care industry and training.

“People at the hospital were saying, ‘Dr. Kiser (the surgeon Joe Kiser, our founder) brought another group of patients.’ In the hallway of the hospital, I saw children squatting down, with blue fingers and blue lips – typical Tetralogy of Fallot patients.” A few years later, in 1988, John joined Joe Kiser’s team.

John knows the exact number of children that Children’s HeartLink brought to Minnesota for heart surgery: 642 patients from 23 countries.

“These patients came from Korea, Greece, Ethiopia, Kenya and other places. As we tried to address those patients’ needs, there were changes at the hospitals in their own countries. The pediatric cardiac programs in those countries felt more and more pressure to increase the number of patients while experiencing a lack of resources and the need for highly trained staff. As hospitals started recognizing the value of enhancing their own programs, we started getting requests for training,” says John.

The difficult decision to discontinue bringing kids to Minnesota for treatment was made in the early 1990s.

“One of the reasons was the cost increase. The other reason was the length of time the children had to stay in Minnesota: six months or more. Often, we had to treat other medical problems first, such as give them dental care, before we could do surgery. Additionally, there was a problem of insufficient diagnosis: we kept getting children that were misdiagnosed in their own countries.”

Children’s HeartLink improved the lives of individual children, but the pediatric cardiac programs in the countries these children came from still needed improvement. To change that, medical missions to underserved countries began. Children’s HeartLink also began to wrestle with the missing piece, which was training local medical teams.

“To do that, Children’s Heartlink recruited high-quality pediatric cardiac teams who were willing to donate their time. We focused on a commitment to improving pediatric cardiac services. We wanted to collaborate with a local team during our medical trip, not just treat their patients. Over the years, Children’s HeartLink emphasized training more and more,” says John.

Changing its approach, Children’s HeartLink faced new challenges. There were language and cultural barriers; the need for infection prevention and equipment maintenance, and ineffective program management. The biggest challenge was building and maintaining a critical mass of competent team members.

“At one point we had a really good nurse in Kenya, and she was immediately recruited by a hospital in the UK. Losing one good person could diminish the whole program. We started emphasizing the staff’s value to their program, that they were important–and how we could provide value and support through mentorships and connections.”

Learning through experience

The Children’s HeartLink program evolved through experience. “I remember my very first trip to China with John,” says Elizabeth. “We had 10 people and 29 boxes of supplies. John and I met at the airport to grab carts and stack them with boxes. I remember thinking, ‘This is absolutely insane.’”

John explained that in earlier years Children’s HeartLink collected many supplies and equipment that they thought were necessary to support mission trips. “We went to different hospitals around the Twin Cities with a truck and collected a wide variety of unused medical supplies. We packaged it and sent it to our partners. Once we used a new Boeing plane to transport some equipment to Ethiopia. At one point, we even used the military transport.”

Elizabeth said she once took a portable ventilator (breathing machine) in her backpack that she carried on the plane.

Children’s HeartLink began to recognize that bringing a large quantity of supplies did not support the goal of helping our partners become independent. Additionally, countries became more sophisticated and selective about what they needed.

“We realized we should be bringing minimum supplies and working with the resources that were available. In that way, Children’s HeartLink was sensitive to what a hospital normally had to work with,” says John.

Fundraising efforts

Elizabeth came to Children’s HeartLink first as a volunteer and then as a leader, at a time when the organization had some significant financial challenges.

“With John here to provide expertise for our programs, I was able to focus more on fundraising. Once we got stabilized, we knew there was an opportunity to focus more on teaching and training.”

Elizabeth says that initially, the idea of changing the model from caring for individual children to advancing and empowering entire programs was questioned by some, but ultimately, it became clear that Children’s HeartLink could reach more children with an improved model.

“The consequent work when we leave the country would hopefully be much more effective and touch more children.

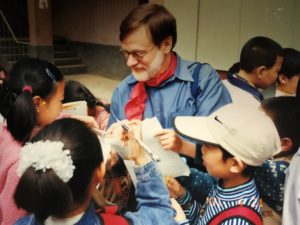

“One of the most magical moments for me throughout all those years was watching the interaction between local, in-country teams and our medical volunteers,” says John.

“To see that interaction was just incredible. We were working with high-powered medical volunteers from Stanford, Mayo Clinic, SickKids (in Toronto). They were willing to not only travel and train but were also more than willing to follow up and be available afterwards as mentors and collaborators.”

The lasting message

An international organization that doesn’t have local charitable programs requires a different strategy to attract attention and fundraising dollars.

“When Children’s HeartLink was bringing kids to Minneapolis, it was easy to write an article about it,” says Elizabeth. “But when we stopped doing that, the remote nature of our work made it harder to share our story.”

Elizabeth says she will always remember the power of seeing our work up close.

“I will never forget my experience of watching open heart surgery in the operating room,” says Elizabeth. “You step up to the operating table, and you are right there, at the head of the child. It was just an unbelievable experience. It is hard to describe, but I could see what Children’s HeartLink is all about at that very moment. This organization has such an impact! That light shining down on that small child. And you see hands working together to save the life of a child. It doesn’t matter who they are or where they are from. Everybody cares only about this child at this moment. That’s the essence of Children’s HeartLink.”

Children’s HeartLink saves children’s lives by transforming pediatric heart care in underserved parts of the world. We currently support 18 partner hospitals in Brazil, China, India, Malaysia and Vietnam. In 2021, our medical volunteers trained over 5,400 professionals and helped more than 122,000 children worldwide. Overall, we have helped over one million children with heart disease. Read more about our work