Published November 4, 2020

One of the first cardiac nurses in Minnesota, Karen Stombaugh began her career in the late 1960s. She remembers her first job in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) as “very nerve-wracking.” Among her patients were adults who underwent open heart surgeries that had become broadly successful only a few years prior. Karen made an impact in Minnesota, by educating other nurses, and she also made her mark outside the U.S., on mission trips to Africa with Children’s HeartLink’s founder and cardiac surgeon Dr. Joe Kiser. After retiring from nursing, Karen followed her passion for art and painting. She has been a steadfast supporter of Children’s HeartLink for decades.

Karen Stombaugh (in the brown and gold) in Nairobi, Kenya in 1995

“After graduation from Swedish Hospital School of Nursing in 1969, I worked in their Intensive/Coronary Care Unit (ICU/CCU). The ICU work was very nerve-wracking at first. I remember having ‘stomach pains’ and feeling in over my head. I also remember some of the difficult assignments: a new patient who was 85 percent covered with burns, another with intestinal rupture after surgery and of course the first open heart surgery patients. These were mainly cardiac valve repairs and replacements. The cardiac surgeons slept ‘on-call in-house’ and we would go down the hall and awaken them if the patient was developing problems.”

At that time, there were no critical care orientation classes for nursing staff, and nurses had to learn on the job. A year later, Karen took advanced classes in cardiac arrhythmias and EKG.

“I became hooked on all things cardiac. It was amazing to me that the voluminous lung organs could be thought of as part of the heart, tucked between its right ventricle and left atrium to oxygenate our blood. I began studying the medical texts and listened to heart and lung sound tapes one summer, even when camping.”

Nursing programs and patient education

Her focus and eagerness to learn led Karen to a position as head nurse of the ICU/CCU at Abbott Hospital in Minneapolis and later at the coronary unit at Abbott-Northwestern Hospital.

“It was very important to me that the nurses become competent and confident in new cardiac technologies and clinical bedside assessments (nursing diagnosis). Equally high on my list of priorities was the concept of total patient care — treating the patients and families with dignity and the awareness of the mind, body and spirit connection.”

As Karen says, the only way to achieve this expertise was “education, education, education and experience, experience, experience.”

“This was done through critical care orientation programs, workshops and mentorships for the novice nurses. We developed standardized care plans that could be individualized to each heart patient. My key innovation was beginning a CCU Nursing Education Fund. I was surprised at how much solicited patients and families gave to our fund. Soon we had enough money for each nurse, regardless of seniority, to attend a national education conference every 3 years. These steps led to increased respect, work satisfaction and retention for our nurses.”

“During an interim job at another hospital, I was concerned that patients were not receiving information about their cardiac conditions, instructions on medications or activity precautions before their discharge. I gathered material from the American Heart Association and developed some of my own hand-outs. I stayed after my shift was over to give this information to patients and families. Word got out. Physicians were surprised at the knowledge level of their patents and their favorable comments about the materials. The doctors decided the hospital needed a patient educator position and offered the job to me. This became one of the first patient education programs in the Twin Cities area.”

To support nurse education and training, learn about our Mary McMahon Busch Nurse Training Fund

A nurse 50 years ago: overcoming stereotypes

When Karen entered the field, nursing was considered a female occupation, and most doctors were men. The nurse-physician relationship was hierarchal, with decision making top-down and non-collaborative.

“Nurses expressed their opinions gingerly. It was better to just give hints. We were not encouraged to think critically or independently. Assessments such as listening to heart and lung sounds were considered a physician’s territory. Orders were not questioned, and this was not necessarily in the patient’s best interest. Nurses practiced in a functional, task-oriented manner. Head or charge nurses rounded with the physicians, carried the charts and saw that physician’s orders were communicated and completed.”

Gradually, physicians came to accept that nurses were uniquely in tune with patients because they were by the patient’s bedside during the most critical moments, day and night.

“The nurse came to be respected as a highly valued member of the medical team. We switched to a nursing care delivery system where the bedside nurse was responsible for administering and coordinating all aspects of the patient’s nursing care. This personalized the patient’s care. Nurses communicated and rounded with the physician on their assigned patients. This was a difficult change to make, and we faced resistance at first from both nurses and physicians.”

Nurses wore white uniforms back then, and nursing caps and white lace oxford shoes–no scrubs or colors. There were no computers.

“We relied on the Kardex, a large folded card within a portable metal file that gave instructions for care and orders for all the unit patients. It was written in pencil, then continuously erased and updated. Central venous and arterial pressures (reflects the ability of the heart to pump the blood into the arterial system) were measured with water manometers. There were no IV pumps. Nurses used their second-hand wristwatches to time intravenous drip rates (the IV flow rate). These were controlled by clamps on the IV tubing. If the needle in the patient’s vein moved, the medication could drip too fast, causing serious reactions.”

Nurses’ salaries were low and benefits were almost nonexistent.

“Things improved after the 6-week city-wide nursing strike in 1984,” says Karen. This was one of the largest nurses’ strikes in the Twin Cities.

Children’s HeartLink and Africa

Karen first met Dr. Joe Kiser in 1969 in the ICU/CCU at Swedish Hospital.

“There was talk of a talented new heart surgeon coming to town, and it was Joe.”

Dr. Kiser was a surgical partner of Dr. Frank Johnson’s. Dr. Johnson’s son sent the first child from Vietnam to the U.S. for heart surgery. That’s how the history of Children’s HeartLink (at that time Children’s Heart Fund) began — bringing children from Vietnam to the US for heart surgery.

The Children’s Heart Fund nurse volunteer (Children’s HeartLink’s name until 1994) with one of the first patients from Vietnam, in Minnesota in 1969

“Our paths continued to cross after that. In the mid-1980s and the 1990s, I worked as a cardiac nurse clinician at the Minneapolis Heart Institute. We cared for the Children’s Heart Fund patients after surgery. I hugely enjoyed this part of my job and have special memories of these foreign patients. In 1994, Dr. Kiser asked if I would be interested in joining a Children’s HeartLink’s volunteer medical team going to Kenya.”

Children’s HeartLink had been working with the cardiovascular program at Nairobi Heart Clinic and Hospital since the mid- 1980s, with cardiologists Drs. Betty and Dan Gikonyo.

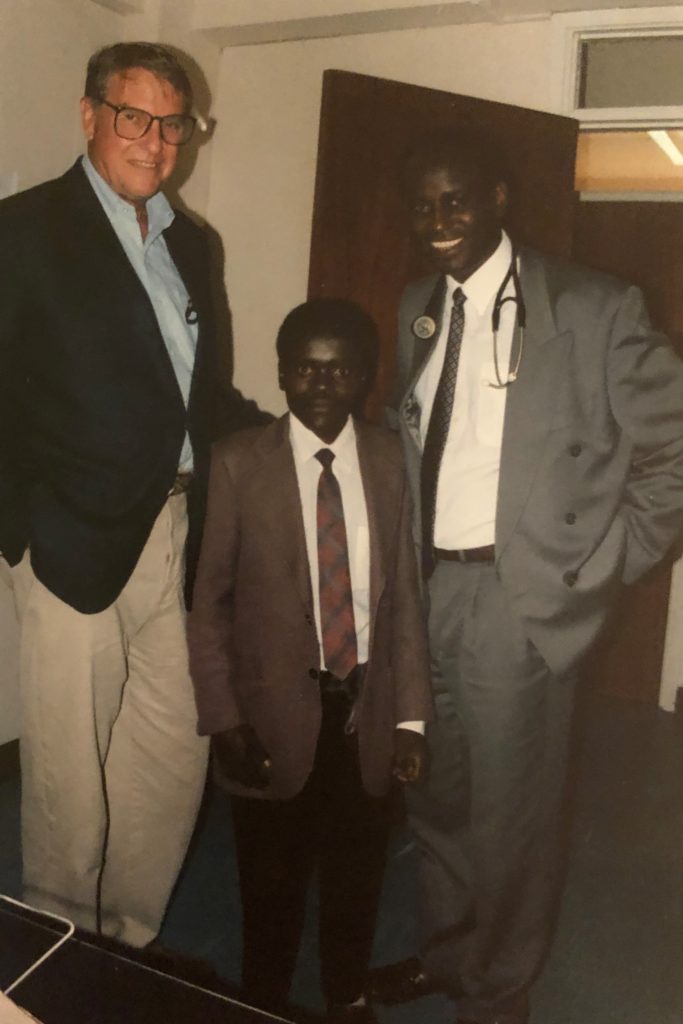

Drs. Joe Kiser and Dan Gikonyo with a patient in Kenya, 1995

“I was privileged to be included in two of these medical trips, in 1995 and 1997. We worked side by side with our Kenyan counterparts and offered assistance and training in open heart surgery on children. We also helped set up a catheterization lab and a rheumatic heart disease prevention program. My specific role was nursing education. On our first trip, three children were operated on: an aortic valve replacement and two atrial septal defect repairs. On the 1997 trip, six surgeries were done. Those included the first pediatric double valve surgery in Kenya, the first repair of Tetralogy of Fallot and the first two coronary artery bypass surgeries!”

These trips were among the most challenging, overwhelming and rewarding experiences in Karen’s nursing career.

Children’s HeartLink medical volunteers with a patient in Kenya, 1997

“There was fear of failure, fear of the unknown, the sleep deprivation that came with travel and the stress of last-minute preparations. There was a fine line between ‘doing with’ and ‘doing for.’ Equipment, blood products, IV fluids and medications were all different enough that one had to be innovative and fall back on basic principles to problem solve. Supplies were limited compared with the US, and I learned quickly to conserve and not be wasteful of what could not readily be replaced.

“I am not sure who gained the most from this experience: it was a beautiful exchange!”

The impact of medical trips was seen in the letters the nurses and children in Kenya wrote to Karen. One of the nurses wrote: “You may not remember me. You are my role model. You shared with us your wonderful knowledge in cardiac surgery. I liked your zeal in life… ready to help patients to the best of your capabilities. I want to work hard to take on the challenges.” And from one of the young patients: “I am becoming a new person. Now I can do all the work which I could not do before like help Mum cook, clean and go to the farm… Also, I am playing with my young sister and brother and running like them. I am doing well in my studies.”

Karen visiting the Indian Ocean, 2019

“Thank you”

While on vacation in India 2 years ago, Karen visited the Amrita Institute of Medical Science in India, a Children’s HeartLink’s Center of Excellence.

“Dr. Krishna Kumar showed me the pediatric cardiac ICUs. I was astounded and humbled by the nurses’ sophistication and professionalism, and with the complexity of intravenous medications, monitoring lines and other life support. I was so proud of them and how advanced pediatric cardiac surgery nursing there has become!”

The main thing Karen would like to tell nurses in underserved parts of the world is “thank you.”

“Thank you for being a good student and achieving your nursing degree in spite of the challenges you faced. Thank you for pursuing the advanced knowledge to become a pediatric cardiac nurse. Thank you for having the courage, inner strength and dedication to continue. Thank you for taking on the additional challenge of the novel COVID-19.”

Karen’s story was published by the International Council of Nurses.

After retiring from a career in nursing, Karen became a professional artist: “Creative art-making was always an integral part of my life and there was never enough time to really develop it. But these art activities immensely helped my nursing. It provided a break from the intensity, stress and burn-out that are inevitably part of the job. It helped me renew and refresh! Another big avocational interest was gardening, and this was equally helpful. I did a series of Art and Garden Shows over the years. Many included fundraising for Children’s HeartLink.”